- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Lion City hopes a new multibillion-dollar facility will help keep it the world’s largest transshipment hub. But there’s a rising tide of pretenders to its crown

Work is slowly winding down at the container terminals in Singapore’s bustling commercial centre.

Giant cranes at the iconic Tanjong Pagar Terminal – long seen as a barometer for the city state’s economic health – are no longer used to service hulking container ships. Instead, they are ready to be dismantled, their parts to be sold as scrap metal.

This is just one step in Singapore’s great port migration to its new, multibillion-dollar home far west of the island: the upcoming Tuas mega-port, primed as the crown jewel of its maritime industry.

Cranes at the Tanjong Pagar Terminal in Singapore. Photo: Xinhua

Cranes at the Tanjong Pagar Terminal in Singapore. Photo: Xinhua

The new port is shaping up nicely, as Singapore holds on to its position as the world’s largest transshipment hub. Reclamation works for the first phase of development are on schedule, with more than 70 per cent of the 221 caissons – 28-metre high watertight concrete structures used to build the wharf – installed as of the end of April, according to the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA). The remaining caissons will be completed by early next year.

In April, the MPA awarded a S$1.46 billion (HK$8.8 billion) contract to a global consortium for the second phase of development at the port, which includes work to dredge the Tuas basin, set up wharf structures and reclaim 387 hectares of land, more than three times the area of Hong Kong Disneyland Resort.

The Tuas mega-port, when completed in 2040, will be able to handle up to 65 million standard-sized containers, up from some 40 million today. It will house all of Singapore’s container activities, running on emerging technologies, automation and data analytics.

Forget China: Hong Kong, Singapore are new kids on the blockchain

This means the city state will be bookended by the port in the west and the airport in the east, buttressed by yet another mega infrastructure plan in the form of Changi Airport Terminal 5, Singapore’s largest airport terminal yet.

WHY MOVE?

Like many other ports around the world, the Port of Singapore began life from the heart of the city, which in the past served as a focal point for trade and cargo.

The lease for Singapore’s three city terminals – Tanjong Pagar, Keppel and Brani – expires in 2027, and the land that will be freed up will be redeveloped as part of the Greater Southern Waterfront project, a sprawling 1,000 hectare area with mixed land uses.

Since 2016, Singapore’s port operator PSA has begun to relocate operations from the city terminals to the newer Pasir Panjang Terminal, which will host most port activities until Tuas is operational, starting from 2021. The lease for Pasir Panjang will run out in 2040.

Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar Terminal, pictured with Sentosa Island in the background. Photo: Bloomberg

Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar Terminal, pictured with Sentosa Island in the background. Photo: Bloomberg

A PSA Corporate spokesman said Tanjong Pagar, Singapore’s oldest terminal, is being used for ancillary services, while container operations continue at Keppel and Brani.

The move to Tuas is strategic.

Industry watcher Tan Hua Joo, executive consultant at Alphaliner, said the new port would help Singapore cope with the anticipated growth in container volumes.

“There is insufficient land at Pasir Panjang to accommodate additional future growth as well as the eventual relocation of cargo from the city terminals when their leases expire,” he said.

He added that the move to Tuas would allow Singapore to retain its position as the leading container transshipment hub in Southeast Asia.

The Tuas port is designed to accommodate mega-vessels that can hold 24,000 standard-sized containers or more, with its long linear berths and deep-water capabilities.

The port is also to run on the latest port technologies and systems. A fleet of 30 automated guided vehicles have already been deployed at the Pasir Panjang Terminal in a trial, along with automated yard cranes and quay cranes.

All of this comes at a time when competition between ports continues to intensify, each vying to anchor big shipping alliances, while digitalisation is driving change in big waves in the maritime industry with big data and automation.

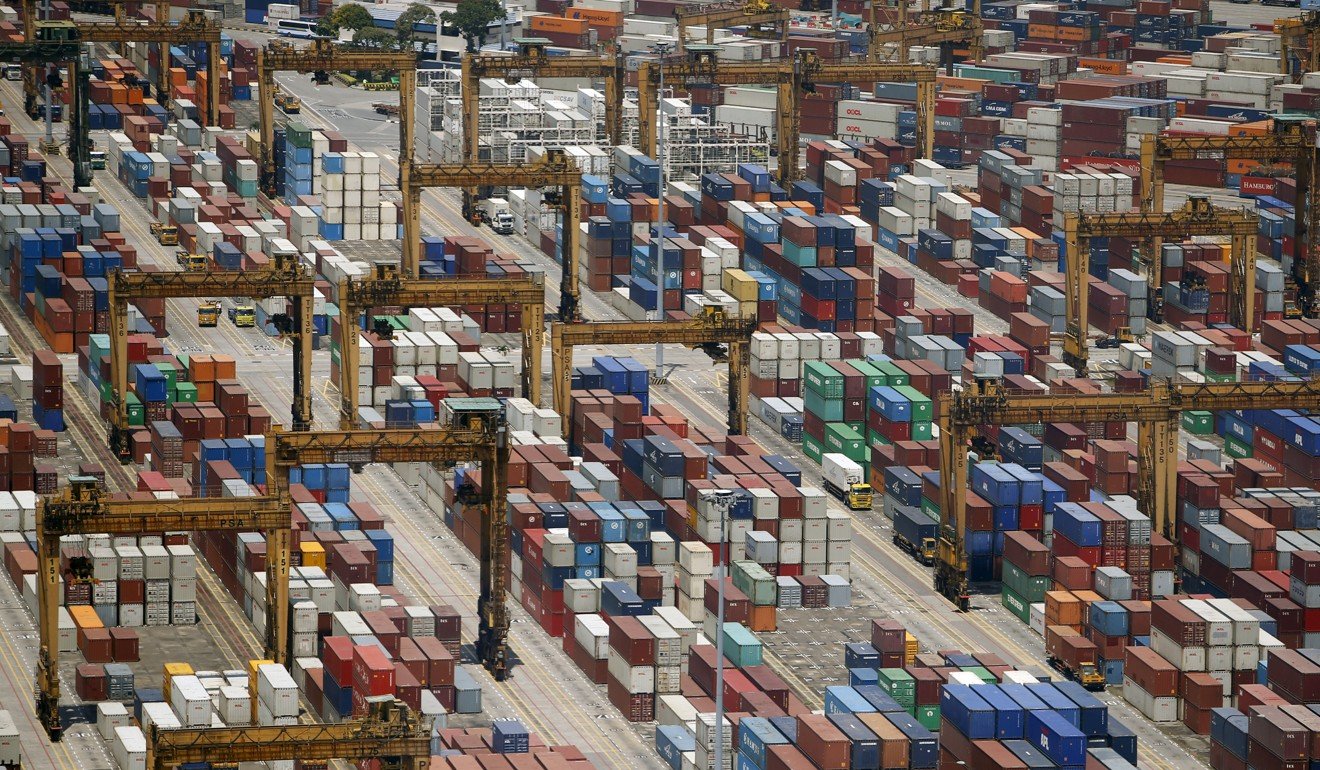

Containers at the Tanjong Pagar Terminal in Singapore. Photo: Reuters

Containers at the Tanjong Pagar Terminal in Singapore. Photo: Reuters

An MPA spokesman said the new port reflects the government’s approach of planning for the long term, while remaining responsive to new developments and opportunities. Tuas was a good location because of its “sheltered deep waters, and proximity to both major domestic industrial areas and international shipping routes”. “Consolidation of the container port activities at Tuas will achieve greater economies of scale. The new port at Tuas will also be able to provide additional capacity to meet the needs of the industry,” he said.

Amid concerns that port activity will be tucked away and out of sight at the western end of the island – and overlooked by the public – the MPA has said the maritime industry will remain a pillar of the economy.

What has given Singapore a taste for Hong Kong cooking?

Singapore did well to cement its dominant position as the port of call in the region last year, having anchored major names in global shipping such as France’s CMA CGM. Japan’s newly-minted Ocean Network Express has also parked its global headquarters in the island.

Container throughput rose 8.9 per cent to 33.7 million containers in 2017, while the maritime industry employed more than 170,000 people and contributed 7 per cent to the economy.

Even so, that doesn’t mean everything will be plain sailing for the Lion City. Alphaliner’s Tan said it would have to watch out for regional competitors, such as the Malaysian ports of Klang and Tanjung Pelepas, while Ocean Shipping Consultants director Jason Chiang noted that Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand had also invested heavily in modern deep-water facilities, which has resulted in larger vessels calling directly at these ports. “This means cargo can skip being transshipped at a port in the Strait of Malacca altogether and go straight to Vietnam, for example, which is cheaper,” Chiang said, adding that while Tuas was a “necessary move”, other factors like competition and slower economic growth would always be a “wild card”. ■

http://www.scmp.com/week-asia/business/article/2148878/singapores-tuas-mega-port-plain-sailing-ahead